Anatomy

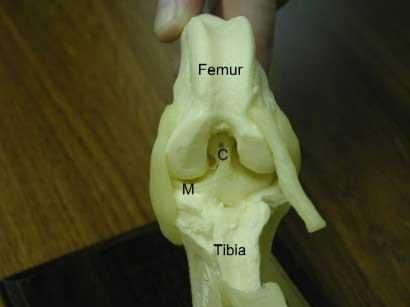

- The cranial cruciate ligament (CCL) is one of the main stabilizing structures of the stifle joint (in man this joint would be called the knee). The CCL serves to prevent forward movement of the tibia bone (shin bone) relative to the femur bone (thigh bone), to prevent internal rotation of the tibia bone, and to limit overextension of the stifle.

- Two meniscal cartilages located inside of the joint are crescent-shaped pads that serve as cushions, provide stability to the joint, and help to push the nourishing joint fluid into the cartilage of the femur and tibia bones.

- Several other ligaments also hold the stifle together; however they infrequently rupture in dogs.

- Below is a photo of the ligaments of the stifle joint as viewed from the front - the kneecap and patellar ligament have been removed; C=cranial cruciate ligament; M=medial meniscus

Cranial cruciate ligament rupture

- CCL rupture is the most common orthopaedic condition that we treat and affects all breeds of dogs, and occasionally cats.

- In dogs the cruciate ligament tends to undergo degenerative changes that weaken it prior to rupturing. This is in contrast to people, where rupture is often associated with an injury such as skiing or playing football. This important difference explains why treatment options in dogs are quite different to those in people.

- The reason the cruciate ligament degenerates prior to rupturing is not clearly understood. Certain breeds, such as Labradors and Rottweiler’s, are much more commonly affected than others. This suggests there is an inherited component to the condition, possibly related to conformation or gait.

- Partial ligament tears may be difficult to diagnose and frequently occur in both legs at the same time.

- Rupture of the CCL is associated with the development of osteoarthritis within the stifle. This occurs in every case and is often evident by the time the dog is examined and X-rayed (radiographed). Osteoarthritis tends to be a progressive disorder and it is dubious whether treatment of the CCL rupture reduces or stops this progression.

- Many dogs with CCL rupture tear their cartilages (or menisci) within their knees. This is similar to the situation in people. Torn cartilages can be very painful. The response to painkillers can often be poor. Surgery to remove the damaged section of cartilage is generally necessary.

What are the signs of cranial cruciate ligament rupture?

The signs of CCL rupture can be quite variable as rupture may be sudden and complete, or gradual and partial. The key signs are hind limb lameness and stiffness. The latter is generally most evident after rest following exercise. Difficulty rising and jumping are common features in dogs with both knees affected. Occasionally ‘clicking’ noises may be heard.

How is cranial cruciate ligament rupture diagnosed?

Examination may reveal muscle wastage (atrophy), especially over the front of the thigh (the quadriceps muscles). Thickening of the stifle is often palpable. Manipulation of the joint may enable the detection of instability. Flexion and extension of the joint may cause pain. In some cases palpation under sedation or light anaesthesia may be necessary to enable the detection of more subtle instability of the knee as occurs with partial rupture of the CCL.

Radiographs provide additional information, especially regarding the presence and severity of osteoarthritis. Specific views may be necessary to assess the angle of the top of the shin bone (the tibial plateau) prior to possible surgery.

In selected cases it may be necessary to take a sample of fluid (synovial fluid) from the knee and send it to a laboratory for analysis. This enables the detection of any inflammatory changes such as occur with infection and rheumatoid arthritis.

How can cranial cruciate ligament rupture be treated?

- Some dogs with CCL rupture can be managed satisfactorily without the need for surgery. The smaller the dog, the more likely it is that this approach will be successful.

- Exercise needs to be restricted. Hydrotherapy is often beneficial.

- Dogs that are overweight benefit from being placed on a diet. Tit-bits may need to be withdrawn and food portions reduced in size. Regular monitoring of weight may be necessary.

- Painkillers (anti-inflammatory drugs) may be indicated to make the dog more comfortable. Long-term drug therapy should be avoided if at all possible in view of potential side effects.

- Many medium, large and giant breed dogs with CCL rupture benefit from surgery. The key types of surgery are (1) CCL replacement (2) TTO and (3) meniscal (cartilage) surgery.

1. CCL replacement surgery

The conventional treatment for CCL rupture in dogs has been to replace the ligament with either a graft or an artificial ligament. Graft replacement is commonly performed in people following anterior cruciate ligament rupture where, as previously mentioned, the cause of the rupture is generally injury. In dogs an artificial ligament is more commonly used, and that is the technique we perform here. The long-term stability provided by artificial ligaments in large dogs with degenerative rupture of their ligaments is questionable. As a result we recommend that the use of this replacement technique is limited to smaller, lighter dogs and in other, specific, circumstances.

2. MMP Surgery

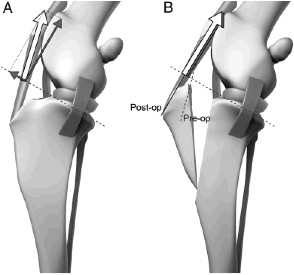

In large dogs, the speed of recovery and the reliability of the soft tissue repairs is more of a concern due to the larger forces operating in the joint and also on occasions due to anatomical irregularities. In recent years several procedures have evolved, all of which alter the angle of the top of the tibia in relation to the pull of the thigh muscles through the patellar tendon.

MMP stands for Modified Maquet Procedure. In this procedure, a cut is made in the front of the tibia to allow the patella tendon to move forward and a honeycomb wedge of titanium is secured behind the cut. This a very secure repair and alters the angle of the joint so that the damaged ligament is no longer important. It is especially suited to athletic dogs that like to run a lot.

This picture demonstrates the issues with angle in the dog’s knee that can predispose to cruciate disease. Image B shows how the cut can correct this problem.

This picture demonstrates the issues with angle in the dog’s knee that can predispose to cruciate disease. Image B shows how the cut can correct this problem.

This is a post-operative x-ray showing the implants (see below) in place

This is a post-operative x-ray showing the implants (see below) in place

3. Meniscal (cartilage) surgery

Cartilage injury, as in people, can be a significant cause of pain and lameness. The damaged section needs to be removed (known as a partial menisectomy). This is usually done at the same time as one of the above surgeries, although it can be done as a standalone procedure in certain circumstances. If cartilage is not damaged, a procedure called a meniscal release is usually performed to try and prevent future cartilage injuries.

Expected convalescent period

- By 2-4 weeks after the surgery your pet should be touching the toes to the ground at a walk.

- By 6-8 weeks the lameness should be mild to moderate.

- By 6 months after the surgery your pet should be using the limb well.

Success rates

- With either technique, the vast majority are significantly improved from their preoperative state. Success is nearly always down to choosing the best option for your pet, so please discuss your concerns with one of our orthopaedic surgeons (Colin Lindsay or Dan Lewis).

- The techniques will not stop the progression of arthritis that is already present in the joint. As a result, your pet may have some stiffness of the limb in the mornings. In addition, your pet may have some lameness after heavy exercise or during weather changes.

Potential complications

- Anaesthetic death can occur, but is very rare

- Infection at the surgical site

- Premature loosening or breakage of the nylon bands; snapping of the plate or screws (dependant on technique used)

- If the meniscal cartilages were not found to be damaged at the initial surgery, it is possible that damage may occur at a later date, thus requiring a second surgery. The sign of a meniscal tear is a sudden onset of lameness.

The Other Limb

- About one third of the dogs will also tear the cruciate ligament in the opposite limb.

- These dogs frequently have arthritis in the knee joint even before the tear in the cruciate is obvious on physical examination, but early changes such as mild joint swelling may be detected with x-rays.

- An x-ray may be recommended to predict if the opposite stifle joint is going to develop a tear.